Unguided Girlhood: A Review of “The Blurry Years” by Eleanor Kriseman

October 23, 2018 | blog, book reviews, news

By Christine McSwain

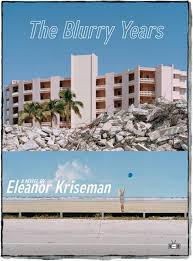

The Blurry Years

By Eleanor Kriseman

160 pp. Two Dollar Radio, $15.99

In The Blurry Years, Eleanor Kriseman depicts the particularly tumultuous but ultimately universal growing pains of Callie, a bright young girl living in Florida with her flighty, alcoholic mother. Against a rotating backdrop of run-down motel rooms, the homes of short-term boyfriends, gas station bathrooms, and decrepit apartments, Kriseman stages a coming-of-age story with an underlying misery that invites the reader, nevertheless, to hope for a happy ending for the novel’s young narrator.

This graceful debut spans the years of Callie’s adolescence, lingering in the tender spots of memory which sting until the end. Throughout her titular “blurry years,” Callie’s mother moves swiftly from one boyfriend to another, one sour ending to the next, and Callie is left alone to cope with her feelings of alienation and adolescent uncertainty without the comfort of her mother’s sympathy. The novel is distinctly interior. What shines here is Callie’s withdrawal into herself and the creeping invasion of her mother’s capricious personality into her own rationalizations. In these moments of introspection, Kriseman’s prose shines. “I thought to myself how dangerous it could be to set your value at what you thought you might deserve,” an eighteen-year-old Callie ponders, one of many profound thoughts from this young narrator. Callie is wise beyond her years but not overly precocious, clearly polished somewhat through the friction of her transient and often loveless home life.

Callie’s quiet examination of herself is wise yet innocent, biting, but ultimately true. This striking honesty is what brings Callie’s internal struggle to the forefront of the narrative, eclipsing melodrama. Callie’s candid weaving of her own narrative is undoubtedly bleak but appropriately evocative, and Kriseman expertly navigates girlhood with her brisk and burning handling of language. “Nobody had taught us anything about becoming women,” Callie says after her best friend Jazz asks her fearfully if she’s ever had “white stuff” in her underwear, the awkward and sometimes terrifying physiology of womanhood a mystery for them both. “We were figuring it out on our own.” Kriseman handles these delicate moments of growing womanhood with poise but never shies away from the horror of it all, the ways in which a girl’s body becomes foreign to her as she grows and changes.

Focused less on Callie’s slip into familiar patterns of destruction, caused primarily by her mother’s detachment, and more on her inner turmoil, The Blurry Years artfully avoids melodrama in favor of intimate character work, seen most prominently in Callie’s thoughts and actions. She describes a walk home from school when the colors of the sky feel too vivid to be real: “I felt like I was watching myself on a screen, acting, waiting for my cue.” It is this consistent derealization, this creeping compulsion to perform and please, which leads Callie through her own narrative, stumbling through her growing years, attempting to resist the path set forth by her wayward mother, only to find herself slipping into the same patterns of self-destruction.

With The Blurry Years, Kriseman tells a story of inevitability and ugly honesty, both deeply personal and unemotionally succinct, propelling Callie forward and simultaneously pulling her back to repeat the same mistakes of the past.