Demand To Be Heard: A Review of Halle Hill’s Good Women

March 14, 2024 | blog, book reviews

Review by Annie Grimes, MFA ’24

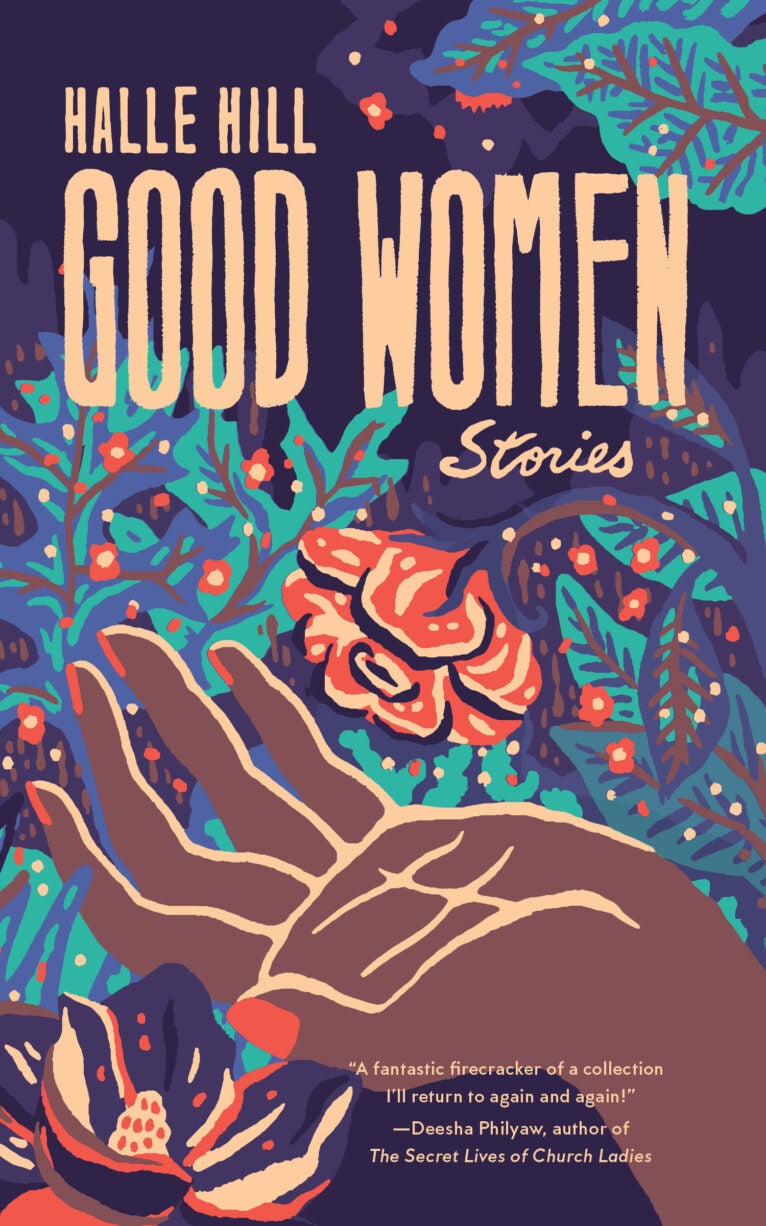

Good Women

216 pp. Hub City Press. $17.95

Good Women, the debut collection of stories from Halle Hill, follows the intimate lives of Black, southern women as they navigate the socially and politically fraught waters of what it means to be, as the title suggests, “good” women.

Across twelve expertly penned stories, which range both in length and theme, Hill fashions her characters with a rich level of empathy and generosity, refusing to sacrifice complexity for flashiness or melodrama.

The opening story, “Seeking Arrangements,” is a nine-page stunner.

It follows Krystal as she rides a Greyhound from Nashville to Florida with a much older white man named Ron, whom she met on a dating site. The story subverts expectation by describing Krystal’s actions not through a lens of disgust, but an abundance of care. Krystal is finely attuned to Ron’s regimen of needs, armed with his “Benadryl, EpiPen, steroids, and inhaler.” She asserts that “whatever he needs, I have. I got him.”

The story ends with a haunting ode to possibility, as Krystal gazes toward the bus driver, LaKeisha—who previously in the story was forcefully grabbed around the neck by a passenger—and imagines a different life for them. “Arm in arm,” she thinks, “we could find our way. I know I could get off right here if I wanted to.”

Subsequent stories track similar emotional arcs, shining light on the lives of women who are not so much trapped in their struggles as they are bound by them.

In “Honest Work,” Maudette is determined to make enough money working at an Eastern Tennessee fair to support her single mother, who has turned to sex-work to make ends meet since her daughter was little.

In “The Truth About Gators,” Nicki attends court-mandated counseling after stabbing the foot of an older church-going man. Out clubbing on weekends, she searches for affirmation in the arms of strangers, attaching meaning to their touch, and conflating their attention with a path toward healing.

Though greatness exists within every word Hill writes, Good Women truly begins to soar around page fifty, with the excellent sequencing of two of the book’s longest and most memorable stories, “Hungry” and “Skin Hunger.”

In “Hungry,” a soon-to-be high school freshman attends local Weight Watchers meetings as her father’s health declines rapidly due to his recent diabetes diagnosis. With a mother who was twice hospitalized for anorexia in high school, she slowly begins to succumb to the devastating demands of a phrase which has been passed down her family line like a precious heirloom: “Nothing tastes as good as thin feels.”

Hill’s gift for conveying significant meaning within the scope of only a sentence is on full display here, as the main character comes to realize that her wants are “just an illusion to be managed,” a lesson that is as disheartening as it is realistic in a world that too often denies the desires and needs of Black women.

Still, even in the face of this denial, the women in Hill’s stories persist, finding ways to meet their needs despite the systems in place to suffocate them.

In “Skin Hunger,” a woman named Shauna secretly remains on birth control as her white husband John grows more and more obsessed with fathering a child. Aware of the status she occupies among his family and all-white social circle, she promises herself to “never bring a child into a family that [doesn’t] want her.” This silent rebellion lays the foundation for a reading experience riddled with tension and righteous deception.

Not afraid of risks, Hill’s stories often take many well-crafted leaps, placing women in situations they need to escape, but offering little guarantee they will be able to escape them. However, it is imperative to note Hill refuses to reprimand her characters for the conditions under which they live. Instead, she respects them enough to treat them honestly; to give them dignity when life is anything but fair, and their choices are anything but free.

In what is perhaps the collection’s most unique story, “The Best Years of Your Life,” Hill illustrates this authorial dignity with precision.

The protagonist, an advisor at a for-profit, non-accredited university, “helps” an older white woman gain acceptance into the program. “I get so sad cause I lie to people every day to pay my bills,” she admits. Out of gratitude, the white woman takes the advisor out for dinner. “After we get seated,” the story details, “she has me go first. Tells me to get whatever I want.”

In stark contrast to the young girl’s experience in “Hunger,” the ending of “The Best Years of Your Life” seems to argue that the protagonist’s wants are not an “illusion to be managed,” but an important matter worthy of being met.

As I turned the pages of this book in rapt attention, I was continually impressed by the complexity Hill was able to weave into every plot point and character. In my opinion, the word “quiet” has been overused when praising the power of stories that detail the complexities, sorrows, struggles, and triumphs of the inner lives of women.

The stories in Good Women, although mostly quotidian in subject matter (and there is indeed something to be said about the quotidian nature of sexual abuse, misogyny, fatphobia, racism, police brutality, and so on), demand to be heard, not because they are loud, but because they tap into the realest parts of what it means to be human. Of what it means to be alive. Good Women is a collection I will return to again and again, and Halle Hill an author that has cemented her place on all of my future shelves.